Science, Translated:

Go With Your Gut

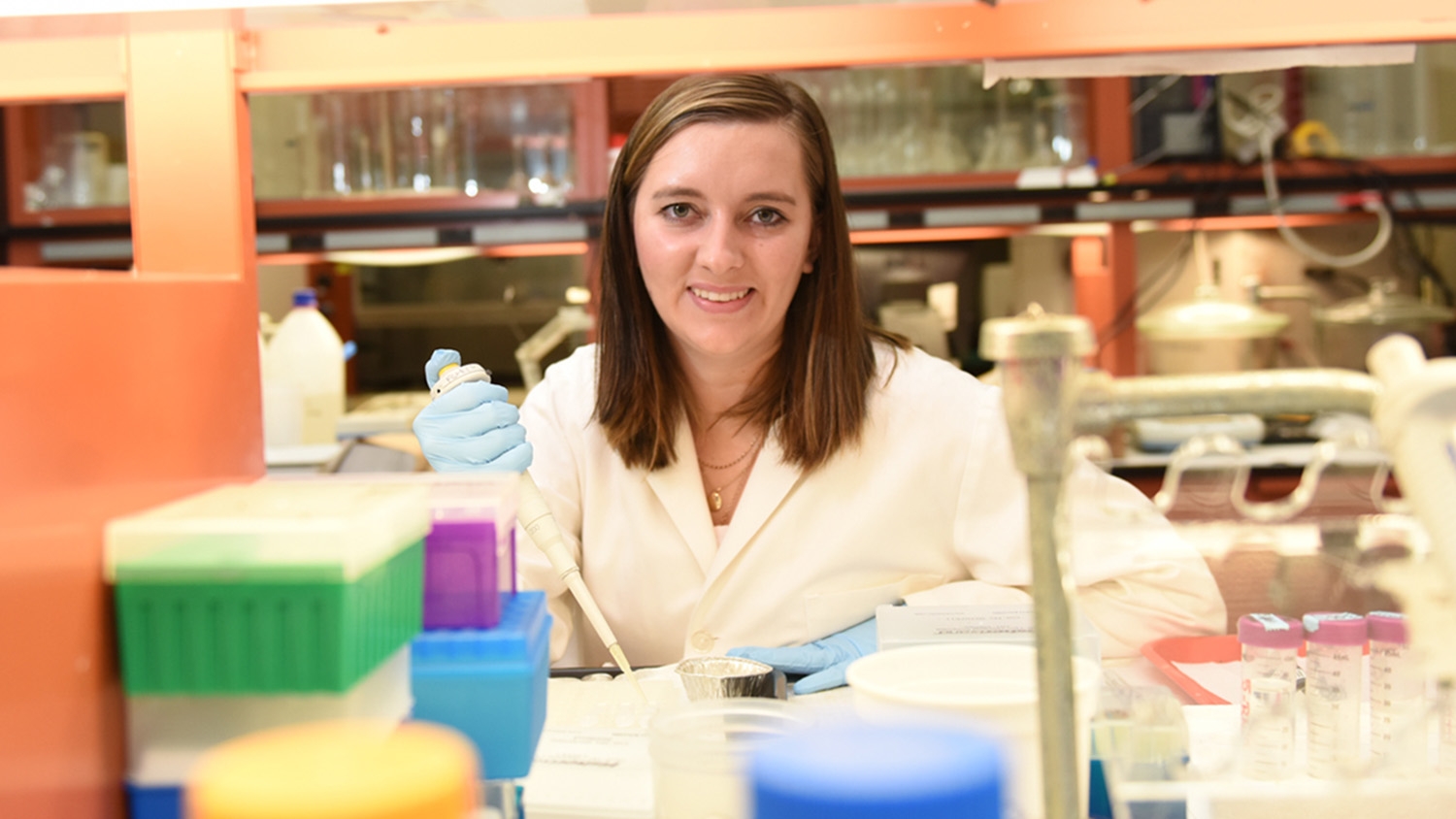

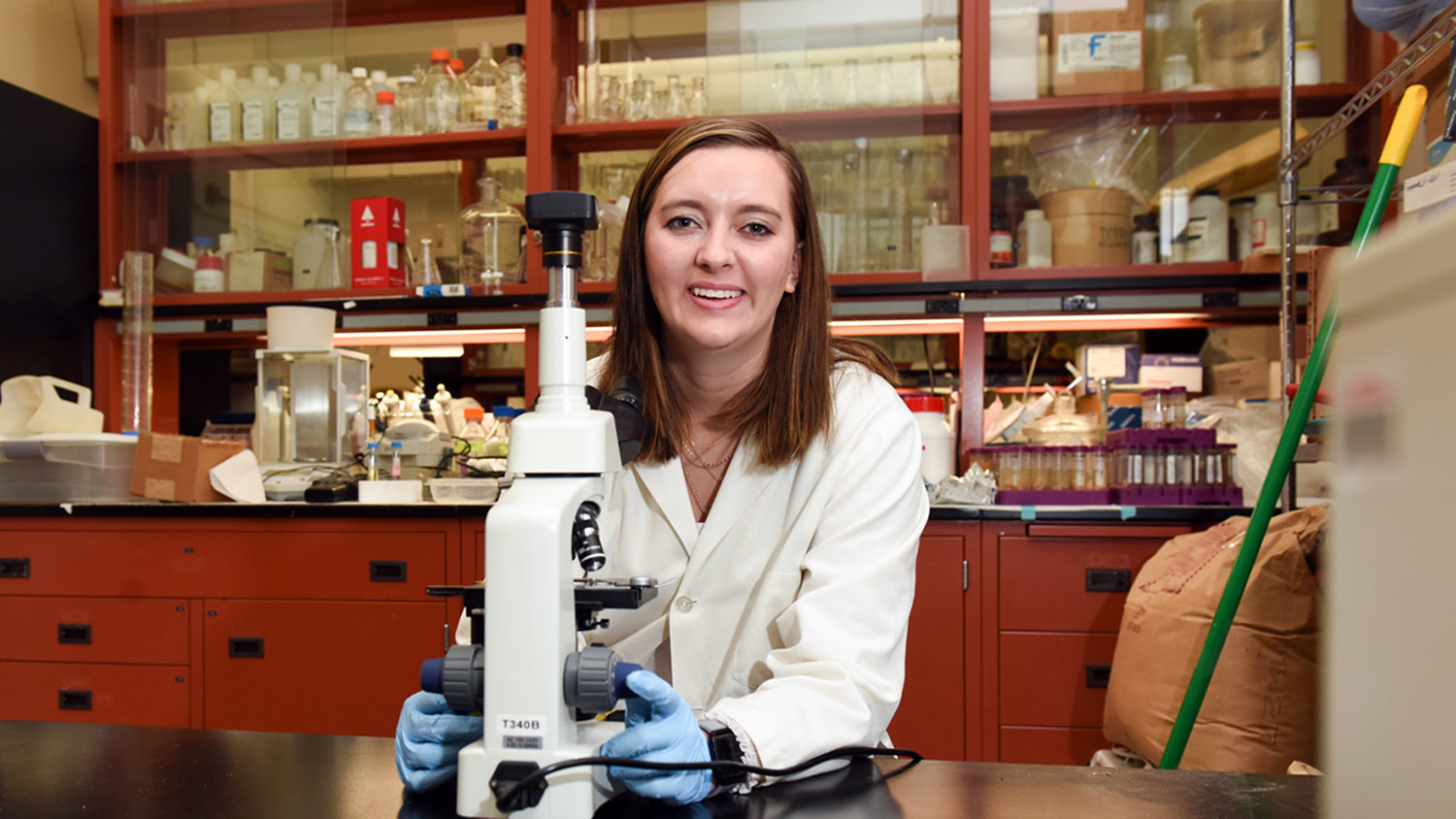

In our new series, Science Translated, CALS Magazine brings you scientists in their own words. If you’d like to request a topic or researcher for our next issue, please email the editor at chelsea_kellner@ncsu.edu. First up: Marissa Herchler of the Prestage Department of Poultry Science.

“You are what you eat.” Ever hear that saying? We’re beginning to figure out just how true it is: scientists are uncovering previously unsuspected ways we’re affected by our guts and our diets.

My contribution: I study the gut health of adult turkeys because they closely represent what we see in humans. My current research focuses on enzymes, the biological substances used in turning food into energy. We produce enzymes that help us digest our food, but sometimes adding supplemental enzymes will increase digestibility. By feeding our turkeys antibiotic-free diets with supplemental enzymes and studying the results, my research team hopes to learn how to predict digestive health.

One of the most interesting parts of my research is the fact that “gut health” itself isn’t well-defined, because it impacts so many systems in the body. How do you measure something that expansive?

Solving the puzzle

Wait, what's an enzyme again?

How to talk like a poultry scientist

Wanna sound like Marissa (or at least understand her work a little better)? Listen up:

Enzymes: Biological molecules that speed up the rate of chemical reactions, including turning food into energy

Gene expression: The process by which genetic instructions are used to synthesize proteins or other products

Neural network deep-learning algorithm: Used to identify patterns or connections between data points or sets; helps scientists make predictions that might be overlooked using other methods

As a scientist, I love these kinds of big problems – because I love helping solve them. With funding from CALS’ new Animal Food and Nutrition Consortium, my latest research will use neural network deep learning algorithms.

Translated, that means we’ll upload our information to a database that uses software to cross-reference correlations among multiple data sets instead of just one at a time. This will allow us to identify patterns or associations in the digestive system that might otherwise be overlooked.

We’ll start by measuring different genes in the gut based on varying levels of enzymes in the turkeys’ feed. We’ll examine the genes’ characteristics when we “read” each turkey’s DNA. We’ll determine the levels of specific genes present in each turkey’s intestinal tract. Then we’ll compare that data with our growth measurements.

In addition to human health implications, this will also help us address a big question for the turkey industry: Is there a link between the patterns of certain genes and how well birds grow?

Research in action

As a scientist, I love big problems – because I love helping solve them.

We weigh the birds and their feed every other week. This helps us track their growth. We also do daily checks for animal welfare. This type of research wouldn’t be possible without a great deal of teamwork: in this case, farm managers, CALS employees, undergraduate and graduate students, advisors, technicians and anybody else willing to pitch in.

Our goal is always to increase the flocks’ fitness in ways that don’t compromise their immune systems in the long run. In learning how to use algorithms to predict animals’ health, we can use more natural and holistic additives rather than antibiotics or traditional disease management.

The big picture

More and more, we are learning that our guts are connected to our physiological characteristics; this type of research allows us to use algorithms to understand those connections. As we increase the amount of data available to study, we can also increase the accuracy of our predictions.

And that’s how it works: one data point at a time, building a more complete understanding of the healthiest way to live.

CATEGORIES: Animal and Ecological Systems, Extension, Research, Spring 2019

View Comments 0