I Am CALS: Emily Reed Hunts the Mosquito Superhighway

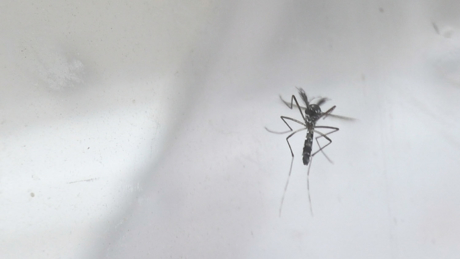

A stowaway sneaked aboard trans-Pacific cargo ships en route to the United States in the 1980s: the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, the most aggressively invasive mosquito species in the world.

CALS doctoral candidate Emily Reed suspects that those ships aren’t the only human infrastructure hijacked by the tiny bloodsuckers for their invasion.

Working in the Department of Applied Ecology, Reed is studying how our own sidewalks and roads may correlate to Aedes albopictus’ travel and spread.

“This has the potential to impact how we manage our invasive mosquitoes,” Reed says. “This has the potential to inform how we design our cities and improve quality of life.”

Using the same cutting-edge toolkit that allows genealogy companies to track down human family trees, Reed compares the genetic signatures of different populations of mosquitoes to see how closely related they are. Then she looks at the geography between those populations.

“My hypothesis was that there’s this human-mediated travel, so that … our human infrastructure and our hard surfaces somehow allow mosquitoes to spread more than they would on their own,” Reed says. “On the flipside, I also want to identify … what’s stopping them from getting from point A to point B or being genetically connected.”

Like many invasive species, the Asian tiger mosquito is extremely adapted to live around humans. That’s why it’s able to exploit our infrastructure to spread. First, it lays its eggs in puddles. The eggs dry out, then hatch when reimmersed in water. In the 1980s, Aedes albopictus eggs laid in tires in Asia crossed the Pacific and hatched in the United States, right around the time Reed was born.

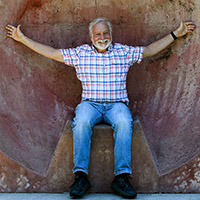

Reed grew up in rural Chatham County, North Carolina, and had nightmares about insects as a child. As she grew, however, she developed a fascination with the complexity of bugs you can find under any log or rock in a walk through the woods. If you like larger animals, she now notes, there’s no guarantee you’ll spot one in the woods; but those who love insects will always have an exciting hike.

Wake County is ideal for Reed’s studies in the Department of Applied Ecology. It’s in the center of Aedes albopictus’ U.S. range, for one, so she’s engaging a larger population. Reed can test her paved surfaces hypothesis on the busy network of roads and highways connecting Raleigh’s urban core with the populous surrounding suburbs.

For her work, Reed sets mosquito traps at sites from gas stations to forest glades. She analyzes genetic samples and pores over urban maps.

And the Aedes albopictus isn’t the only invasive mosquito under Reed’s microscope.

Palm Beach County, Florida, is the southern tip of the Asian tiger mosquito’s range, and it’s forced to share territory with Aedes aegypti — the yellow fever mosquito. It’s a dynamic place to study invasive mosquito populations, Reed says.

All this is a far cry from Reed’s original career path. She spent her first three years of college as a French major. “I grew up thinking I should excel in English and avoid math and physics,” Reed says. “I never took a genetics class before I came here, but now I’m a population geneticist. … I’ve learned to be a lot more confident

in myself.”

CATEGORIES: Animal and Ecological Systems, Fall 2019, I Am CALS, Research

Interesting article. Important work that is meaningful and could be life changing.