Regaining What’s Been Lost: Kamal Bell’s Work at Sankofa Farms

At Sankofa Farms, doctoral student Kamal Bell looks to agriculture and to the past to break down educational barriers for young African American men.

For the Akan people of Ghana, the word “sankofa” is associated with a symbol: a mythical bird with its feet planted forward, its head turned backward and its mouth holding an egg. The word’s translation: It’s OK to go back and get what you forgot.

The word reminds Kamal Bell that there’s wisdom, power and hope in knowing his African roots, and it calls him to share that knowledge with the younger people who will shape our future. Bell puts the word into action as a farmer, a teacher, a mentor and a doctoral student in agricultural and extension education at NC State.

Bell, 29, is founder and CEO for the 12-acre Sankofa Farms in Orange County, North Carolina. There, he raises leafy greens and other vegetables for people who live in communities without easy access to healthy foods. He also raises honeybees.

But there’s much more to his farm than agricultural production.

“I did not want to just have a regular farm where we produce food and went to a farmers market,” he says. “I wanted to have more of a meaningful impact.”

And there are clear signs on his farm that this unconventional farmer is having just such an impact.

The Journey to a Mold-breaking Farm

Kamal Bell doesn’t come from an agricultural background, and the path to farming wasn’t a straight one. As a child growing in Durham, he loved reading about animals and being outdoors, and that led him to study animal science at North Carolina A&T State University.

There, he gained experience on a university research farm, where he learned about organic vegetable production. Then he interned with a Black farmer. “That’s really when my interest in agriculture started to be cultivated,” he says.

He went on to earn a master’s degree in agricultural education from A&T and taught agriscience at a middle school in Durham. There, he saw his students gravitate toward the garden, and that interest coupled with his desire to bring healthy food to areas without it grew into Sankofa Farms.

The Hum of Bees: the Voice of the Farm

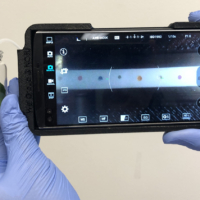

At the farm, 40 beehives that Bell keeps are central. In addition to pollinating the plants he grows, the bees produce income. Bell sells honey on the internet, and he’s preparing to offer beeswax. He also rents hives, offers an in-person introduction to bee-keeping called Bees in the TRAP—short for Teaching Responsible Apiary Practices—and has launched an online course called Honey at Home.

The bees also play an integral role in Bell’s highest priority on the farm: the fledgling agricultural academy he conducts for African American males ages 11 and up. The students work on the farm on Saturdays, and as they work, Bell teaches them about farming practices, the science and technology of farming and the benefits that farming brings to communities. Most of the students are certified beekeepers.

“Knowing that honeybees can be traced back to ancient Africa, it ties into our overall educational mission at Sankofa,” Bell says. “They’re living. They’re moving. And they can generate revenue for people. The students are interested in that, and so it’s a bridge to education.”

Building a Discipline-spanning Educational Bridge

The bridge that Bell is building around the study of bees and of agriculture spans diverse subjects, from history to the STEM disciplines of science, technology, engineering and math.

“Agriculture is the basis of everything,” Bell says. “So all the concepts at some point come back to STEM. Engineering: students have had to develop and design the caterpillar tunnels we have on the farm. We’ve had to physically build them as well and think about how we can improve upon them.

[Working on the farm] has opened my eyes to the importance of helping your community and helping others.

“The technology: We have a drone out here now, and we’re looking at how we can automate more of the systems at the farm,” he adds. “Then the science—we’re talking about microbiology. We’re talking about microorganisms. And we’re talking about producing food.”

Lessons also center on the importance of public service, Bell says. And those lessons that aren’t lost on 10th grader Mikal Ali, who’s been coming to the farm academy for four years.

Though the work on the farm is hard, Mikal is motivated by the fact that some of the food produced there goes to organizations that are helping alleviate food insecurity in Durham communities.

“Being able to have nutritional food allows you to think better and allows you to have the right energy, allowing yourself to truly think and be the best that you can be,” Mikal says.

Working on the farm, he says, “has opened my eyes to the importance of helping your community and helping others.” When others are counting on you, he adds, “You can’t stop. It’s just ever-running energy.”

‘A Foundation to Grow’

Mikal hopes to channel that energy into becoming a school psychologist to help students face problems at home and in life. He also wants to build a school geared for Black students—a dream he shares with his teacher.

“Having an education center on the farm is the ultimate goal,” Bell says. “If we want to create a sustainable food source, you have to integrate the youth into that. The people aspect is the most important, and the youth are the future. They need the foundation to be able to grow.”

Achieving that sort of foundation won’t be easy, Bell says. It must start with sankofa—going back to the past, understanding African American history and building forward from there. He points to the teachings of the late African American psychologist Amos Wilson.

“He stressed the importance of African Americans using their history and our culture to build institutions for ourselves. That’s where the change for us lies in understanding our culture,” Bell says. “And if we don’t understand our history and culture, we can’t understand the context and why things are going on in the present day.”

When people know their history, Bell adds, they can control their destiny.

If we want to create a sustainable food source, you have to integrate the youth into that.

“That’s not happening in society right now. Someone else has been telling our story, someone else has been dictating how we maneuver, how we develop identity of ourselves. And if we look at it, we can see that those ideas don’t work for us at all,” Bell continues. “The only way that we can begin to recreate and reimagine ourselves is if we learn about who our people are and learn about our ancestors.”

For Bell, the contributions of Africans and African Americans to agriculture are powerful examples.

“How we contributed to the landscape of agriculture has often been lost and been left out. We have such a connection to the land and contributed so much, and I think a lot of the issues that we face today can be solved if we start looking back at agriculture,” Bell says.

That sort of understanding, he adds, can help bring equity to modern food and farming systems and to education.

“We need to start challenging ourselves to restructure how education looks for Black children. It needs to be in Black-led, Black-run, in Black-controlled spaces. We can center education around solving problems for our people, because education is not doing that,” he adds. “That’s the only thing that’s going to work for us.”

Learning as a Way to Overcome Obstacles

As a doctoral student, Bell is focusing on the barriers that keep African Americans from entering agriculture in the United States. He wants to know that because he’s interested in breaking down those barriers.

“Racism is a barrier, and capital is a barrier. Mentorship—there aren’t that many African American agricultural professionals,” Bell says. “Those are just some of the things that I’ve encountered, but as I conduct my studies, I’ll have a better, more in-depth answer.”

Joseph Donaldson, an assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural and Human Sciences, is one of Bell’s academic advisors. He says he expects Bell’s doctoral work to yield a better understanding of how to provide African American men with better college access, academic advising and career development services.

“His work,” Donaldson adds, “creates equity, access and opportunity.” If the students who take part in Sankofa Farm’s academy are any indication, Bell’s efforts are indeed making a difference.

Jamil Ali, Mikal’s brother, says his interactions with Bell and with his fellow Sankofites have grown his skills in self-control, persistence, public speaking, relationship building and integrity. Through his work at the farm, he says he’s also gained an appreciation of self-reliance, tempered with a willingness to accept help.

“Mr. Bell has really taught me everything—not just about farming and beekeeping,” he says. “He talks to us, and he teaches us life lessons … that will be a big help for me in whatever I do in the future.

CATEGORIES: Newswire, Spring 2021

View Comments 0